Colorado is a windy place (although generally not quite as windy as our neighbors to the north in Wyoming). And April is typically a windy month: in much of Colorado it’s the windiest month on average. But this is more a function of how often it’s windy in April, as opposed to the winds being extremely strong. On April 6-7, 2024, however, we saw both: it was windy for a long time, and there were some very intense gusts.

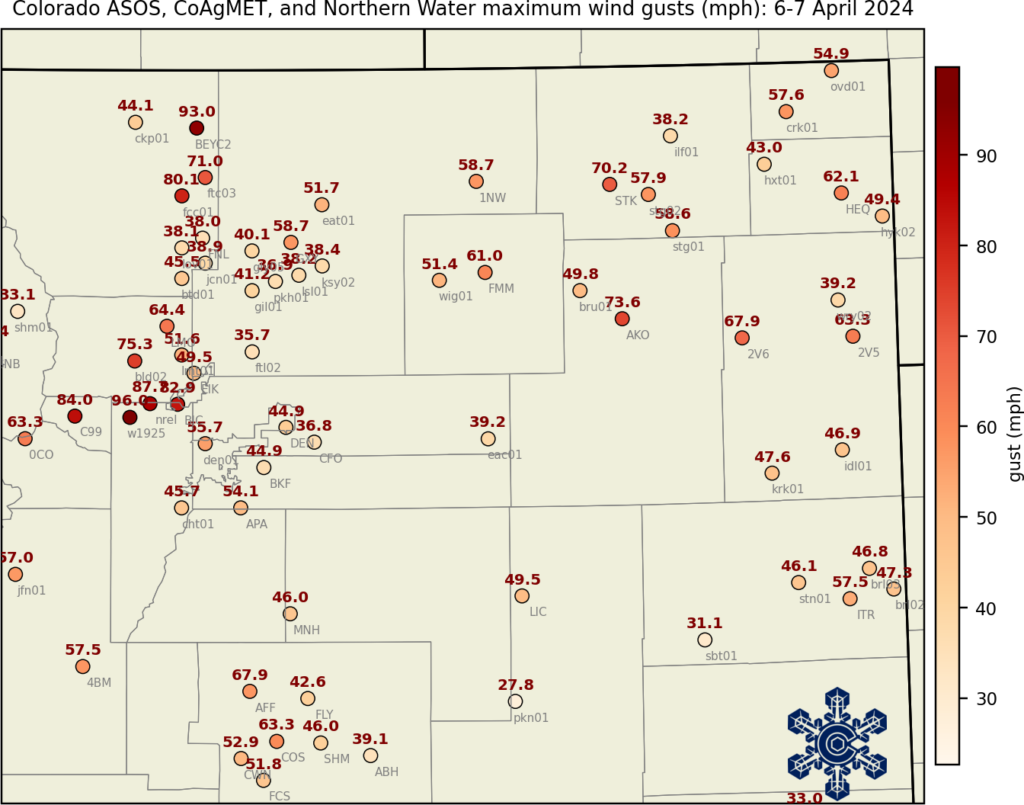

The strongest wind gusts were, as usual, located in and near the Front Range foothills, with gusts above 95mph at NCAR’s Mesa Lab and in Coal Creek Canyon in Jefferson County, and gusts above 90mph in Larimer County. But some intense winds were also recorded on the eastern Plains, with gusts over 70mph at Sterling and Akron.

One weather station that’s useful for looking at strong winds is at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s Flatirons campus. The NREL station is located south of Boulder, an especially windy location. They have also collected weather data a multiple heights every 1 minute since 2001. (See also the update at the end with data from CSU Foothills campus.)

When is windstorm season?

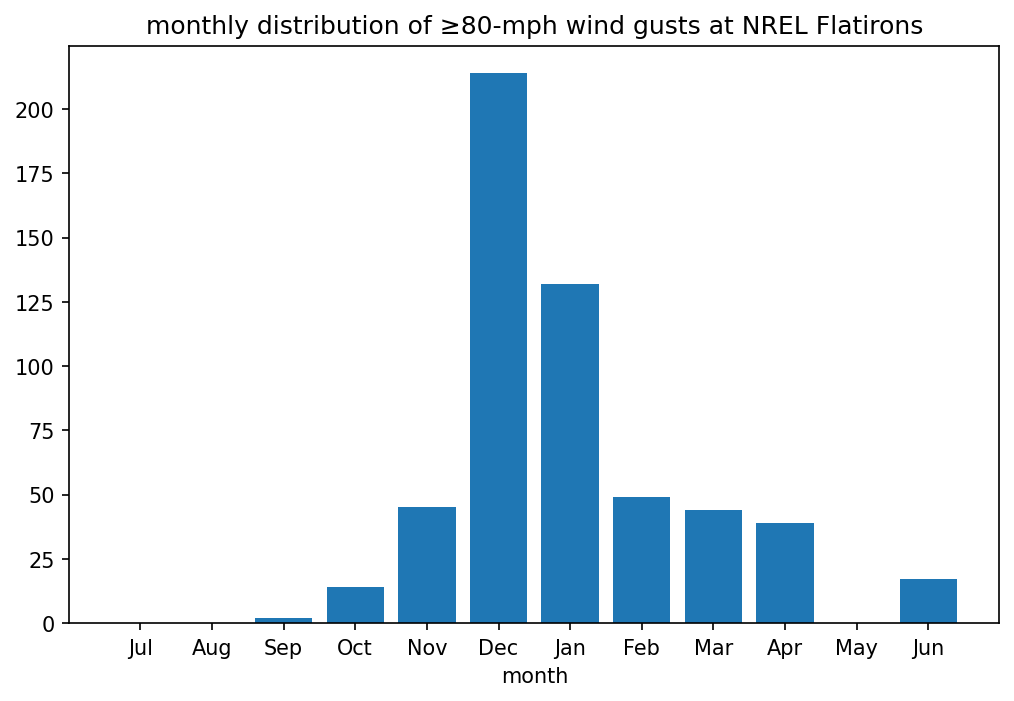

Along the Front Range, especially close to the foothills, the strongest winds tend to happen in winter. At the NREL Flatirons station, the peak is in December and January. (Note that we’re looking at wind gusts of at least 80 mph here — those are very strong winds, and they happen with some frequency at this location!) The windstorm that drove the tragic Marshall Fire in 2021 occurred during this time frame.

This weekend’s windstorm was somewhat unusual in having such strong winds during spring. At the NREL Flatirons station, there were 16 gusts of at least 80 mph on Saturday April 6, and another 19 on Sunday the 7th. These are by far the most for any day in April. The maximum wind gust at the NREL station was 87.7 mph, the highest April value on record at this station. The statistics look similar at other Front Range stations: both a long duration of wind (pretty common in April) and very high wind speeds (not common in April). In much of northern Colorado, this was the worst April windstorm in at least the last 25 years, and more comparable to the types of intense windstorms that sometimes happen in December and January.

How do downslope windstorms work?

Setting the stage for the strong winds was a low-pressure system positioned over western Nebraska. Strong winds from the west and northwest were located over Wyoming and Colorado to the west of this low. But this map shows that the very strongest winds were located at a distance from the low-pressure center, near the Front Range.

The Front Range foothills are especially prone to intense winds as air flows over the high terrain and then rapidly sinks down the steep slopes on the east side. The graphic below is from a short-term forecast from a weather prediction model for early Sunday morning, and illustrates these processes well. On the east slopes of the Rockies, there is a narrow corridor of extremely strong winds (in fact, much stronger than the winds higher up in the atmosphere!) that reaches the surface in the foothills. Just to the east of that, the air “jumps” upward, analogous to what you might see when water rushes over rocks in a stream. These sharp gradients in wind speed are associated with very gusty winds and strong turbulence. The steeper the slopes, the stronger the winds can get, which is why areas west of Boulder (for example, Coal Creek and Eldorado Canyons) experience these windstorms on a fairly regular basis.

The threat of this windstorm was forecast well in advance, with high wind warnings and red flag warnings from the National Weather Service. This led to the first-ever preemptive shutdown of power lines in Colorado, to reduce the potential for fire starts in the intense winds. (This had the side effect of taking down the communications of data from CoAgMET, but things are back up and running now. We apologize to our data users!)

Are windstorms changing?

This is a tougher question to answer. Compared to what is available for temperature and precipitation, there aren’t a lot of weather stations with long, consistent records of wind. (The analysis above is based on about 20 years of data, but for tracking trends and changes we typically need a lot more than that.) The Boulder area has experienced many extreme windstorms over the years, including in the 1970s and 80s, in addition to these recent storms. The unofficial state record wind gust was 201 mph on Longs Peak in 1981, measured at a temporary research station. We addressed the topic of windstorms in the Climate Change in Colorado report, with the short answer being that it’s unclear how windstorms have changed or will change as the climate warms. But with many Coloradans living in areas that are prone to extreme winds, and the known connection between windstorms and the spread of wildfires, we should all be aware and vigilant about the risks.

Update, April 11: data from Christman Field, CSU Foothills Campus

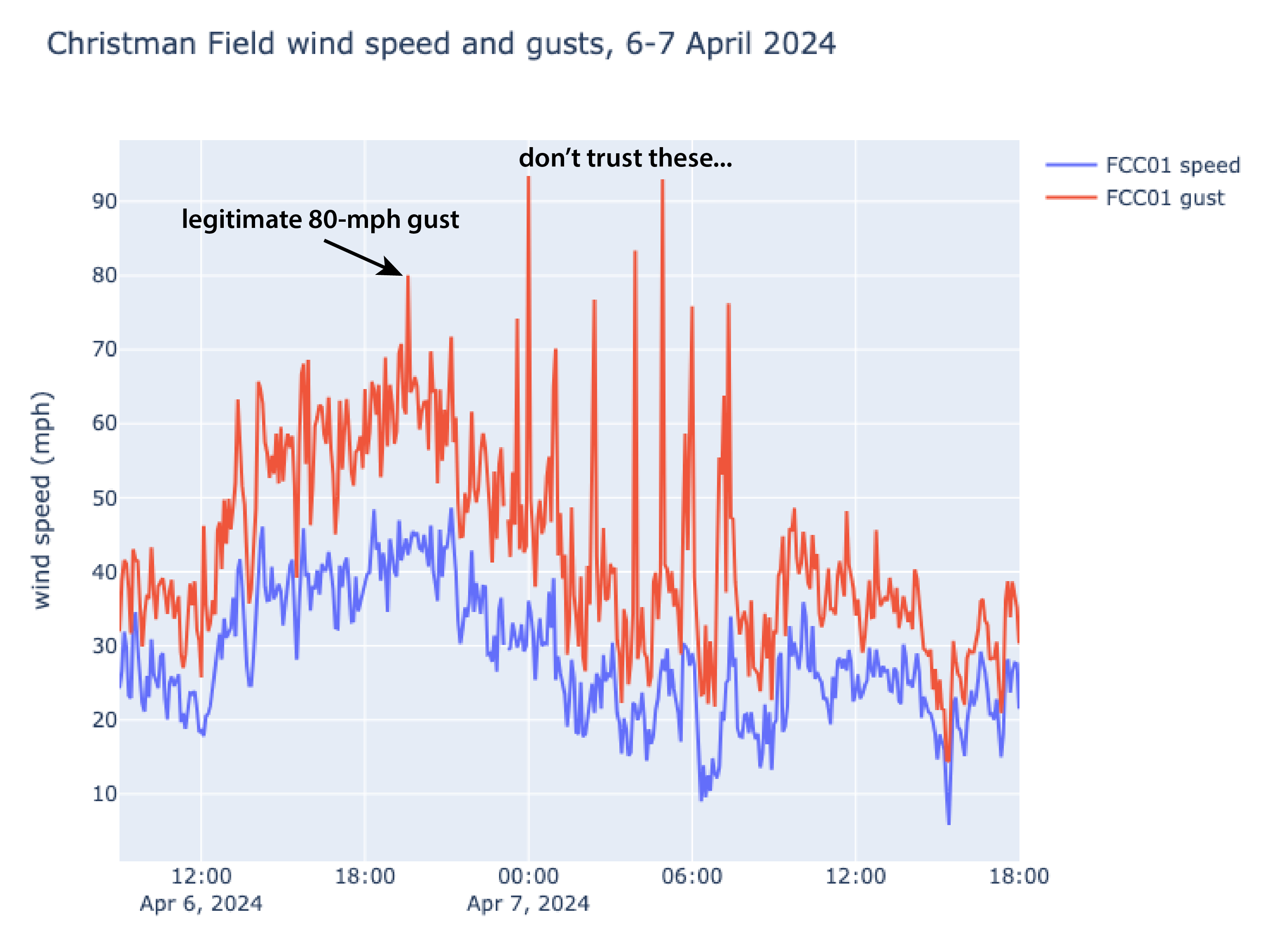

Out at the CSU Foothills campus in western Fort Collins where our office is based, there’s a weather station at the Christman airfield that can get quite windy. The strongest gust recorded at this station was 83.7 mph on December 30, 2008. We didn’t have access to the Christman Field data in real time during the windstorm on April 6-7, because of the power cut mentioned above. When we got the data back online, what first jumped out was a single wind gust of nearly 13,000 mph—obviously an error. After this “blip” in the data (late on April 6), there were several other reported gusts of over 90 mph at Christman Field. At first glance, these seemed plausible, because of the other extreme winds in northern Colorado during this event. But upon closer examination, these gusts after midnight on the 7th look way out of place:

Those gusts are 3-4 times faster than the sustained winds, which is a sign that something is wrong1. In contrast, before the “blip” before midnight, the gusts were generally 1.4-1.8 times the sustained winds, which is consistent with other weather stations. So I think we can conclude that those 90+ mph gusts were a result of an issue with the equipment (either related to damage from the strong winds, issues with the power source, or something else.)

That being said, the data look reasonable prior to midnight. And at 8:35pm on the 6th, there was a gust to 80mph, which is the 2nd-strongest in the history of the station! That one appears to be legitimate.

- Hat tip to Jeff Lukas for this method of looking at wind gusts – he convincingly showed that another purported extreme wind gust, 147 mph at Monarch Pass in 2016, was also almost certainly an instrument error. ↩︎