Climatological fall has arrived, and although September thus far has been much warmer than normal across most of Colorado, it’s still time to be thinking about when the first freeze could happen. Now, those of you reading this from the high mountain valleys might say “silly Front Rangers, we’ve had several hard freezes already,” and you’d be right. Like most other things with Colorado’s climate, there are huge variations across the state in terms of when the first freeze tends to occur.

Let’s start with this map, which shows the average date of the first freeze (temperature less than or equal to 32°F), for stations with enough data to be included in NOAA’s 30-year “normals” for the 1991-2020 period. Stations shown in white have their average first freeze right around October 1, those in blue in September, and those shown in red later in October. The first thing you might notice is that the timing of the first freeze lines up pretty well with elevation: the high country is earlier, the lower elevations on the western slope and eastern plains later.

From NOAA 1991-2020 climate normals, obtained from https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/land-based-station/us-climate-normals

We’ve also highlighted the extremes across the state. Two stations have their average first freeze on September 5: Kremmling in Grand County, and Cochetopa Creek near Gunnison. These stations are located in valleys at high elevation, where cold air tends to pool. Other contenders for the earliest first freeze are similarly situated. (If there were data on top of the 14ers, the idea of a “first freeze” may not be very helpful – they can get below freezing at any time of year!)

On the other end, the latest first freeze is at Palisade, which on average doesn’t drop below 32°F until October 26! There’s a reason that the Grand Valley is known for growing fruit: the “million dollar wind” that funnels into the valley, keeping the air relatively warm, and avoiding hard freezes when surrounding areas often experience them. Other stations around Grand Junction also tend not to have a freeze until late October.

East of the divide, the latest first freeze is in Kim in Las Animas County, with an average of October 18. Most eastern plains locations average a freeze within the first two weeks of October.

What about the years that aren’t normal?

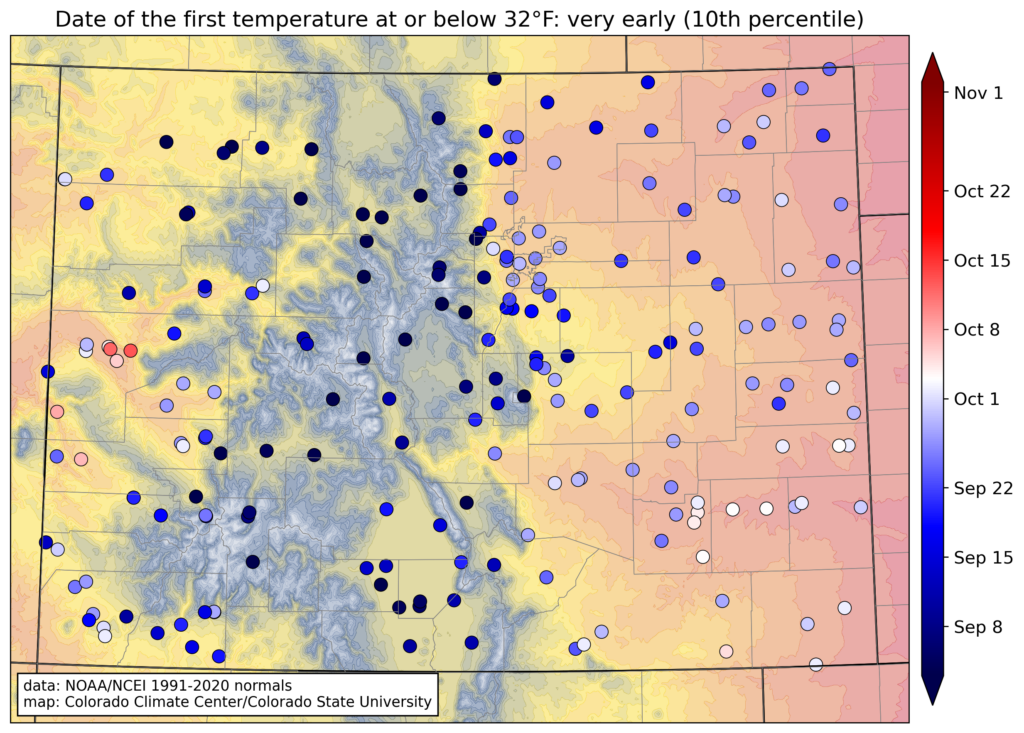

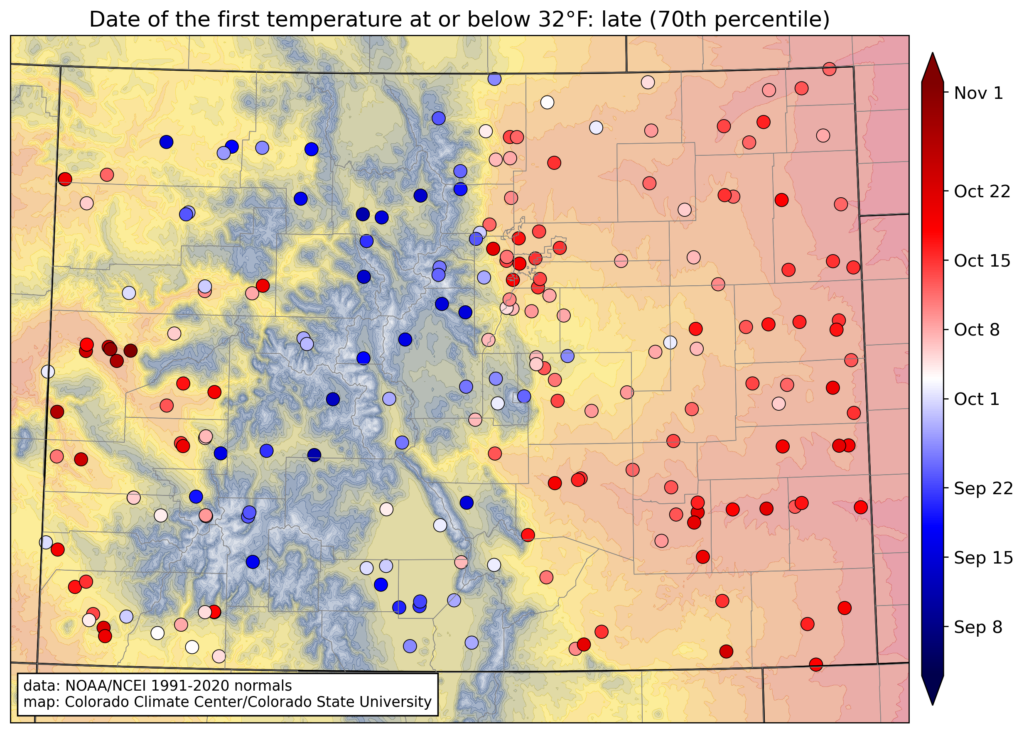

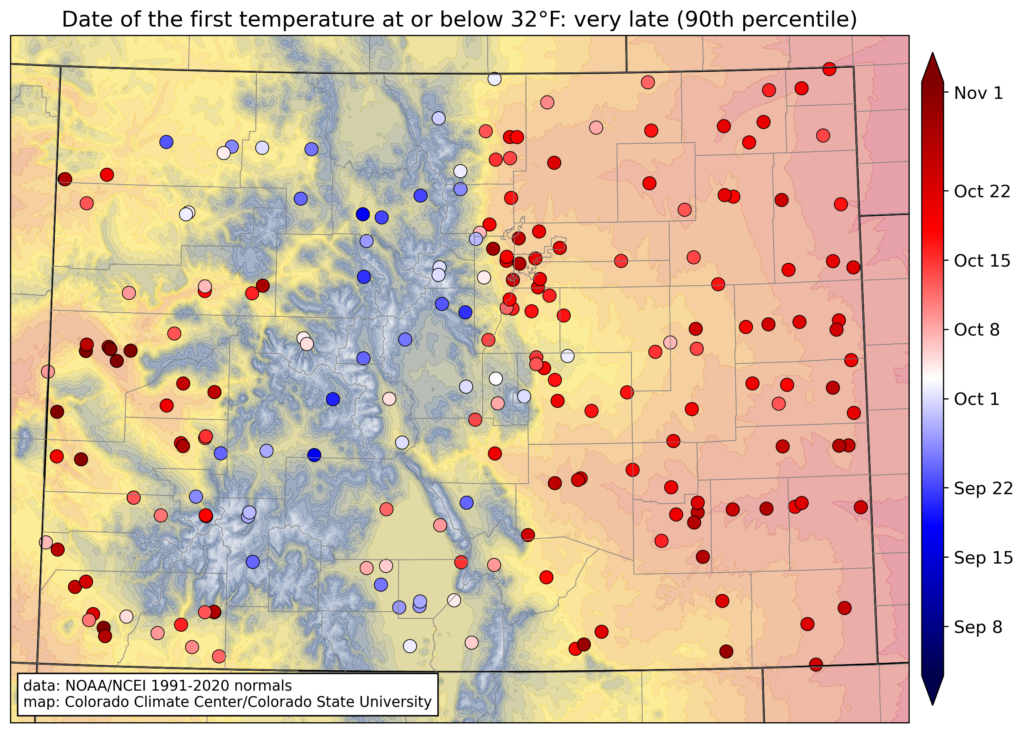

When talking about climate in general, and Colorado climate in particular, we know that we don’t always see the “normal” conditions. So what is the typical range of when the first freeze occurs? NOAA’s normals data also provides the first freeze dates in terms of percentiles. The 10th percentile means that only one out of 10 years would have a freeze that early, and the 90th percentile means that only one out of ten years would have a freeze that late. This set of maps shows the dates of first freezes ranging from the very early to the very late.

The 10th-percentile map shows that nearly everywhere in Colorado can have a freeze in September, with just a couple exceptions. The most notable ones are the Grand Valley (Grand Junction, Palisade), and the Paradox Valley, where a very early freeze would still be in mid-October. (Since 1991, the earliest freeze in Palisade was October 4 in 2016, though there are a few September freezes in earlier years.) In the lower elevations of southeastern Colorado, a very early freeze would be in the first week of October.

Moving to the very late freezes on the 90th-percentile map, the high elevations can’t avoid a freeze in September, but the rest of the state has the potential to wait until mid- or late October, or even until November in the warmest spots. Here is a summary table of the first freeze dates at some locations around the state:

Is the timing of the first freeze changing?

We know that Colorado is getting warmer on average. Summer and fall are the seasons that have been warming fastest in recent decades. But the effect of warming on the timing of the first freeze is complicated. For example, in Grand Junction and Palisade, which has been one of the fastest-warming regions in the state overall, the average date of the first freeze has actually creeped over a week earlier since 1980. In contrast, Front Range and eastern plains locations have generally shifted one to two weeks later. And even with an average shift toward later freezes, it doesn’t completely rule out something like the extremely early cold front that crashed through eastern Colorado in September 2020.

Where to explore further?

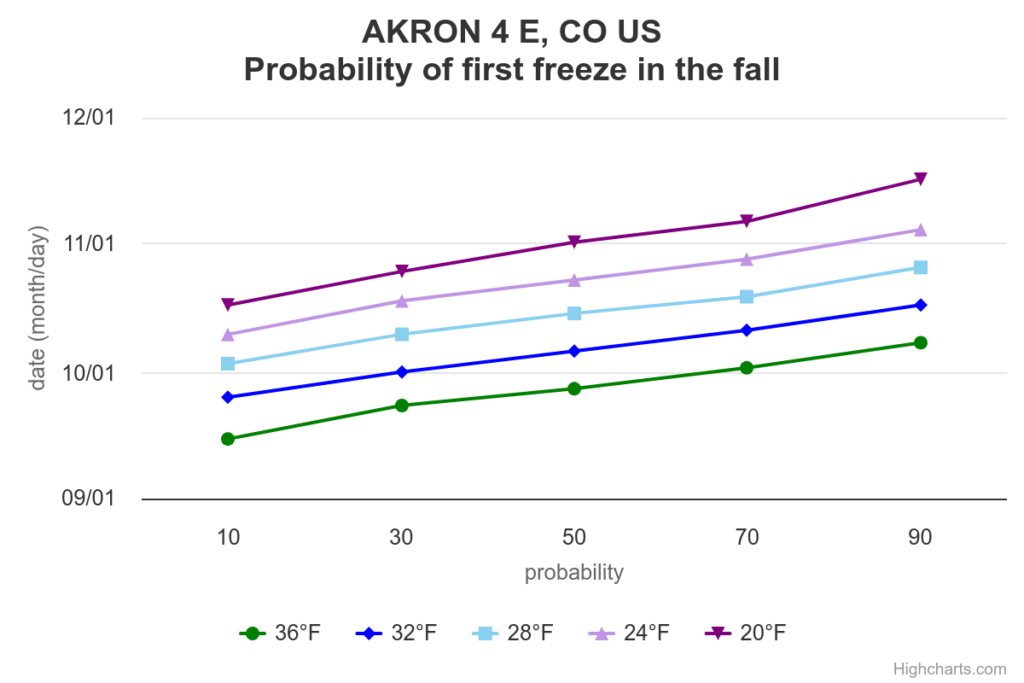

Here, we’ve focused on a threshold of 32°F, but for other purposes, a different temperature might be more relevant (for example, some plants aren’t really harmed by 32°F, but would be at 24 or 28°F.) There are quite a few places on the web where you can find more detailed information, and here are a couple of nice ones from the Midwestern Regional Climate Center. One is an interactive map, where you can enter a temperature threshold and a date, and it will show the probability of a freeze on or before that date. Another is their “cli-MATE” tool, which requires registration, but provides customized graphs of the probability of different temperature thresholds on different dates.

EDIT since first publication: We now have interactive maps showing these frost/freeze dates for Colorado stations on our own website at this link. And you can click on a station to see interactive graphs of the probability of a freeze at each of the stations!

Hopefully this information can be helpful as you’re trying to protect your plans, sprinklers, or just trying to stay warm this fall!