By the time March rolls around, we have a lot of information about how the snowpack accumulation in Colorado’s mountains is going to turn out. For those familiar with statistics, the correlation between statewide snowpack on February 28 and the peak value (usually in early April) is 0.86. For the Upper Colorado River basin, the end-of-February correlation is even higher: about 0.91. This means that, even though March and April can still bring a lot of snow to the mountains, it’s difficult for the spring to turn the tide from a bad season to a good one, or vice versa.

And why do we care so much about snowpack? The water that serves tens of millions of people originates as snow in Colorado’s mountains. Thus, when we talk about “snowpack”, what we’re usually looking at is the “snow water equivalent” (SWE): how much water is stored in that snow, a large portion of which will run off into streams, rivers, and reservoirs in the spring and summer to be used by people, farms, and ecosystems.

Where does this winter’s snowpack stand at the end of February?

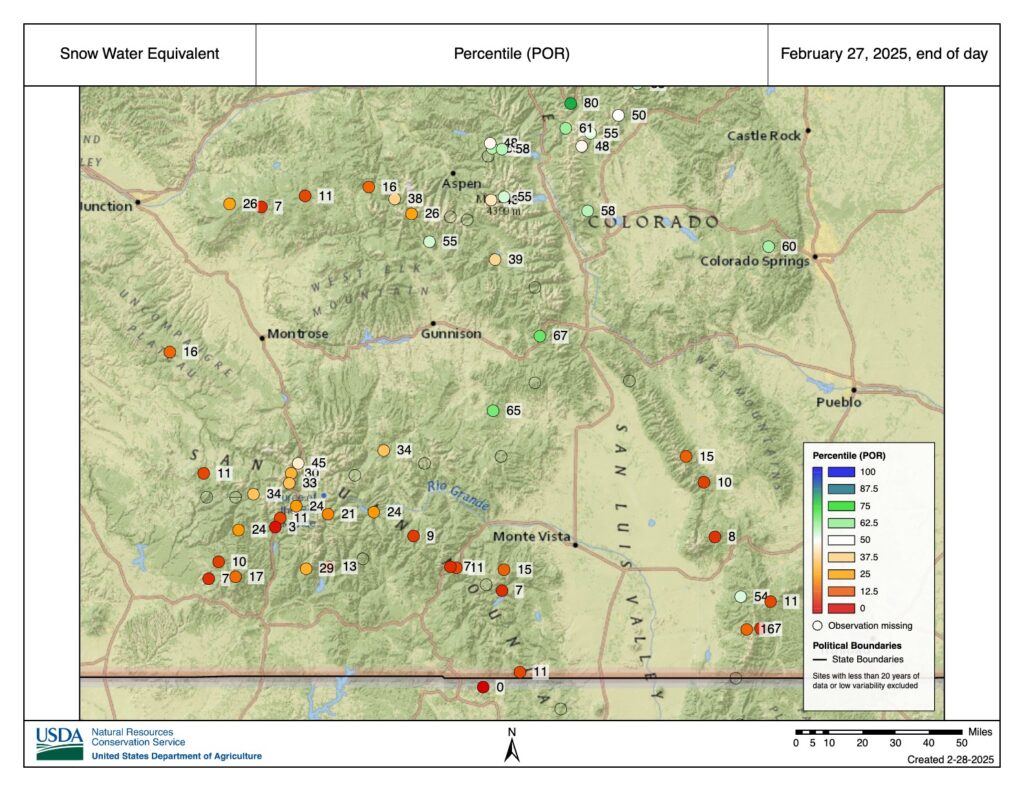

Looking at the current map that shows the percent of median SWE across Colorado, there’s a clear north-south divide. The mountains that will see their water run off into Colorado’s northern river basins like the Yampa, White, and North and South Platte, are looking pretty decent. They were sitting near to a little below average as of early February, but the huge storm cycle in the middle of the month has brought them to right around average, or even a bit above in the South Platte basin.

Farther south, it’s a very different story. Back in November, these areas had way above average snowpack from major early-season storms. But then the snow largely shut off through December and January. Although the San Juan and Sangre de Cristo mountains and the Grand Mesa did get a good shot of snow in mid-February, it wasn’t nearly as much as farther north. And the warm, dry pattern of the last week (at a time of year when we expect regular snowstorms) has left them well below normal. Snowpack in the combined San Miguel-Dolores-Animas-San Juan basin sits at just 66% of average, and the upper Rio Grande at 67% of average.

Zooming in on the southern mountains, and plotting the snowpack percentile over the period of record, we see some very low numbers, especially in the southern San Juans. (Here, if you see a value of 10, that means that 90% of years would have more SWE on this date.) For many stations in Colorado’s southern mountains, the snowpack is the lowest it’s been at this time of the winter since the brutal drought of 2018. (Other seasons that were even worse include 1990, 2002, and 2006.) This week’s US Drought Monitor now shows D3 (extreme drought) in parts of Conejos, Archuleta, and Rio Grande Counties. In contrast, conditions farther north look much better, especially around the ski areas in Pitkin, Eagle, and Summit Counties. The divide of snowier to the north and less-snowy to the south is what often happens in La Niña winters like this one.

Consistent with the snowpack numbers, the outlook for spring and summer water supply looks decent for Colorado’s northern rivers, but pretty bleak for the southern streams, and for the Upper Colorado River basin as a whole. The Colorado Basin River Forecast Center’s mid-February outlook, which largely included the snowpack boost from the mid-month storm, shows near-average April through July streamflows in the Colorado River headwaters, but only 63% of average along the Dolores River, and 70% of average into Lake Powell. Assuming these outlooks end up being roughly correct, there will be a lot less water available in southwestern Colorado (and farther downstream) than in a typical year. CBRFC will host a webinar on March 7 to discuss their updated early-March forecast.

What comes next?

There are 5-8 weeks left in the typical mountain snow accumulation season, depending on exactly where you’re located. March doesn’t always have the consistent mountain snowfall that we expect in the heart of winter, but often delivers a big snowstorm or two. The last week of February has been extremely warm across Colorado, with little to no snowfall, and the first couple days of March will be more of the same. But then the pattern looks to shift to become more active. One storm is on the way for March 3-4, with the possibility of another behind it on March 6-7. But it looks like this may continue to amplify the north-south divide, as current forecasts show the most precipitation hitting the northern mountains and eastern plains, with not as much to the south.

The outlook for March as a whole doesn’t show a very strong signal across Colorado, with only a slight tilt toward below-average precipitation across the southern part of the state. The outlook for the full spring season (March-April-May) shows increased odds of dry conditions across all of Colorado, with the highest chances of dry conditions in the southwest. Overall, in light of the current snowpack and the outlook, for northern Colorado there’s some reason for cautious optimism about the snow and water situation through the spring, but cause for real concern about worsening drought in the south and west.

A note about our federal government partners

If you’ve read this far, you’ve seen a lot of data, and hopefully recognized what it can tell us about the water and drought situation here in Colorado. Every bit of data in this blog post originated from the federal government, either from the Natural Resources Conservation Service (part of the Department of Agriculture), or from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). This information is collected, maintained, and disseminated by dedicated public servants, and is always freely available to all. We work closely with the National Weather Service offices and other NOAA entities that serve Colorado, and their workforce is in the process of being devastated. Those fired include the bright minds of people just starting their careers, as well as experienced professionals who chose to serve the country. We couldn’t do what we do without our federal partners, we stand with them in these challenging times, and want to emphasize that investments in NOAA and other federal agencies support public safety, the economy, and US leadership in science.