For our inaugural post, we’ll take a deep dive into a question that we get asked pretty regularly, and that can cause a fair bit of confusion. (These are the kinds of topics we hope to dive into in future posts!)

A common statistic you might hear in discussions of Colorado water and climate is the “80/20” division: 80% of the water originates west of the Continental Divide, but only 20% of the population lives west of the divide. That means that the numbers are the inverse in eastern Colorado: 20% of the water and 80% of the population.

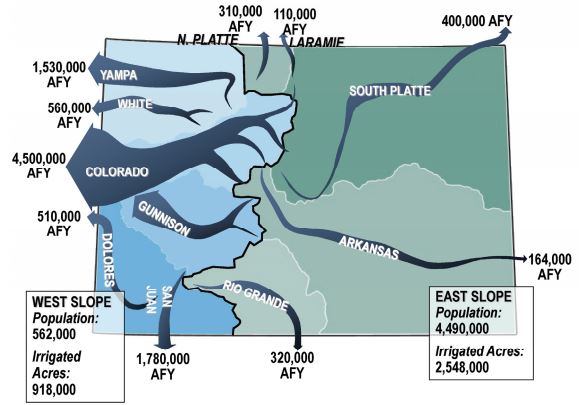

However, these statistics need some clarification, because they often get stretched beyond where they are correct. First: where does the 80/20 statistic come from? It is in fact true for river flows. The specific numbers you get depend a bit on what you’re calculating, for example in this map from the Colorado Water Center that shows flows leaving Colorado, it’s actually even more imbalanced, with about 87% of the flows leaving the state toward the west.

However, when accounting for water used within Colorado, some rivers (especially the Rio Grande and Arkansas) have larger flows upstream than what leaves the state at the border. If using those numbers it comes out to be about 77% west of the divide and 23% east. In any case, both of these are pretty close to the 80/20 split, showing that this statistic is indeed true for streamflow.

(The population numbers on this map are also a bit outdated: using data from the 2020 census, the split in population is now actually closer to 90/10, as western Colorado has grown only modestly, while population along the Front Range has boomed.)

What about precipitation?

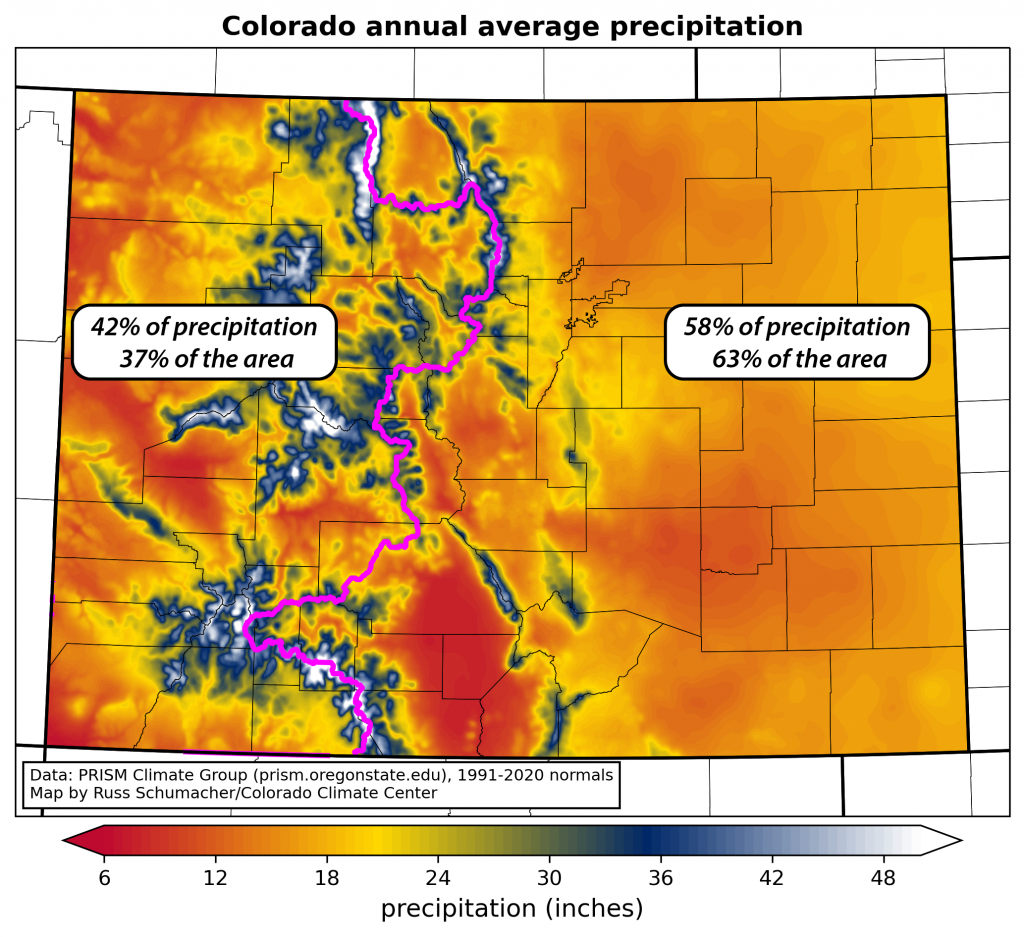

Since the water that ends up in the rivers originates as precipitation, it seems reasonable to expect that precipitation also has an 80/20 split across the Continental Divide. But here’s where the confusion comes in. It turns out that this isn’t even close to being true! How can that be? Let’s take a look at a map of average annual precipitation in Colorado, with the Continental Divide highlighted in magenta.

It is true that most of the places with the largest precipitation totals, such as the Park Range in the northern mountains, or the San Juans in the southwest, are west of the divide. These locations get over 50″ of precipitation per year, in the form of hundreds of inches of snow. This is where the mountain snowpack builds each winter, and then melts and runs off into the rivers in the spring and summer.

But this map also illustrates that, although it tends to be drier than the snowy mountains, there is a *lot* of area in Colorado that’s east of the Divide. So what do the numbers show? On average, only 42% of the precipitation that falls in Colorado falls west of the Continental Divide, with 58% falling to the east. Even though the Rio Grande River flows east, some people might think of that basin being in western Colorado – it’s still only 48% of the precipitation if we include that basin in the “western” calculation. That’s right: less than half of the state’s annual precipitation (on average) falls west of the Divide. The “precipitation per area” is definitely much larger to the west (42% of the precipitation over 38% of the state’s area), but it’s nowhere near 80%.

How can it be that 42% of the precipitation results in 80% of the river flows? This stems from both the type of precipitation, and its seasonality, in different parts of the state. West of the Divide, the vast majority of the precipitation falls as snow in the cool season. The runoff efficiency of the snowpack is very high: when the snow melts in the spring, a large proportion of that water ends up in the streams and rivers.

In contrast, the majority of precipitation east of the Divide falls as rain in the spring and summer. This precipitation largely goes toward helping vegetation to grow and to keeping the soils moist. In other words, this water tends to get used shortly after it falls, and relatively little of it ends up in the rivers (with the exception of big downpours that can lead to a temporary surge.)

The 80/20 split applies to streamflow, not to precipitation

So, to summarize, the 80/20 split across the Continental Divide is true for river flows, but is not true for precipitation. Unfortunately, many documents (including the Colorado Water Plan) conflate these two, and refer to 80% of the state’s precipitation falling west of the Divide. It is understandable why this is a source of confusion, but hopefully this brief analysis can help to clarify and to highlight that most of the water that is available does flow to the west, but precipitation is more evenly distributed.

In next week’s post, we’ll take a closer look at the Arctic blast from mid-January and place it into climatological context.