Leading up to the weekend of July 12-14, weather forecasts were indicating the potential for extreme heat in parts of Colorado. I was getting messages from people saying that their weather apps were showing that all-time records would be broken by multiple degrees (which mostly warranted an eye-roll.) On both Saturday the 13th and Sunday the 14th, there were just enough afternoon clouds and showers to keep the temperatures from reaching historic highs. But it was still a noteworthy heat wave, especially along the Front Range. Fort Collins reached a high of 102°F on Friday the 12th, one degree shy of the all-time record, and only the 7th time in over 130 years of records it had been that warm. That same day, Colorado Springs reached 100°F for only the 12th time, also one degree shy of the all-time record.

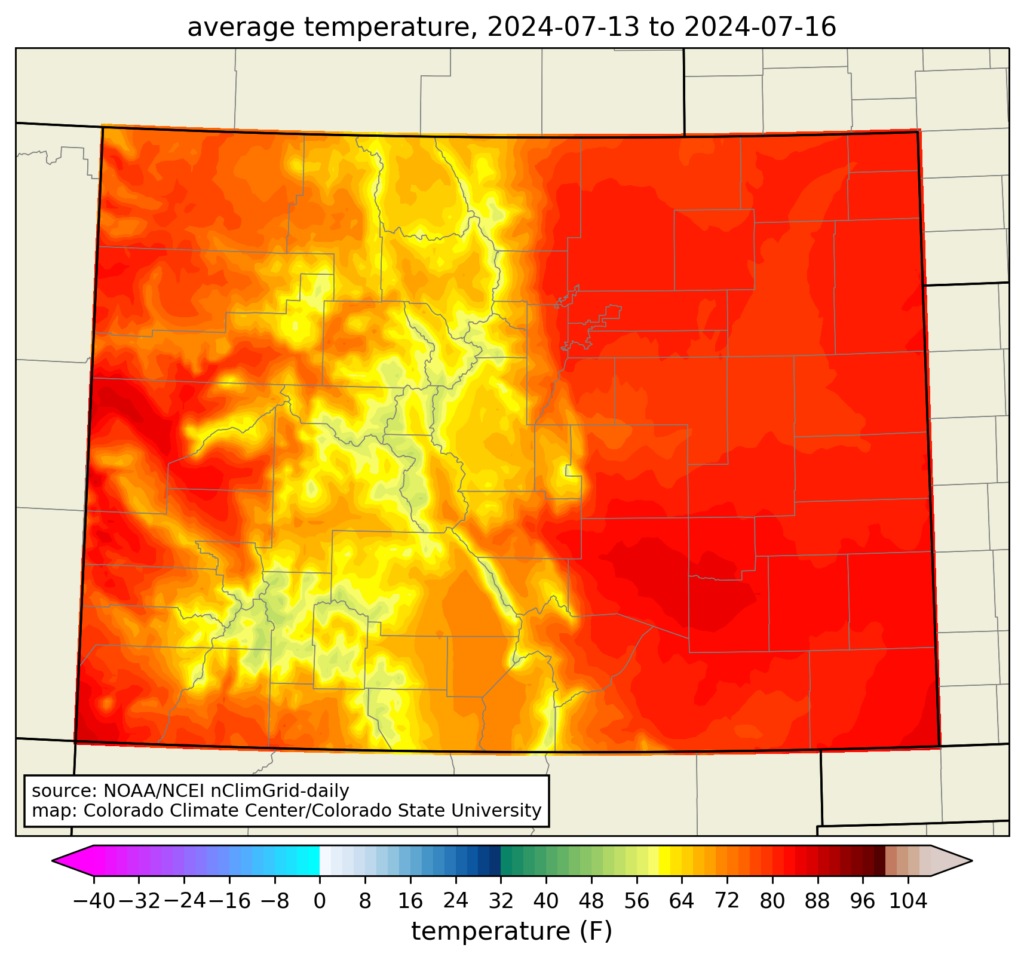

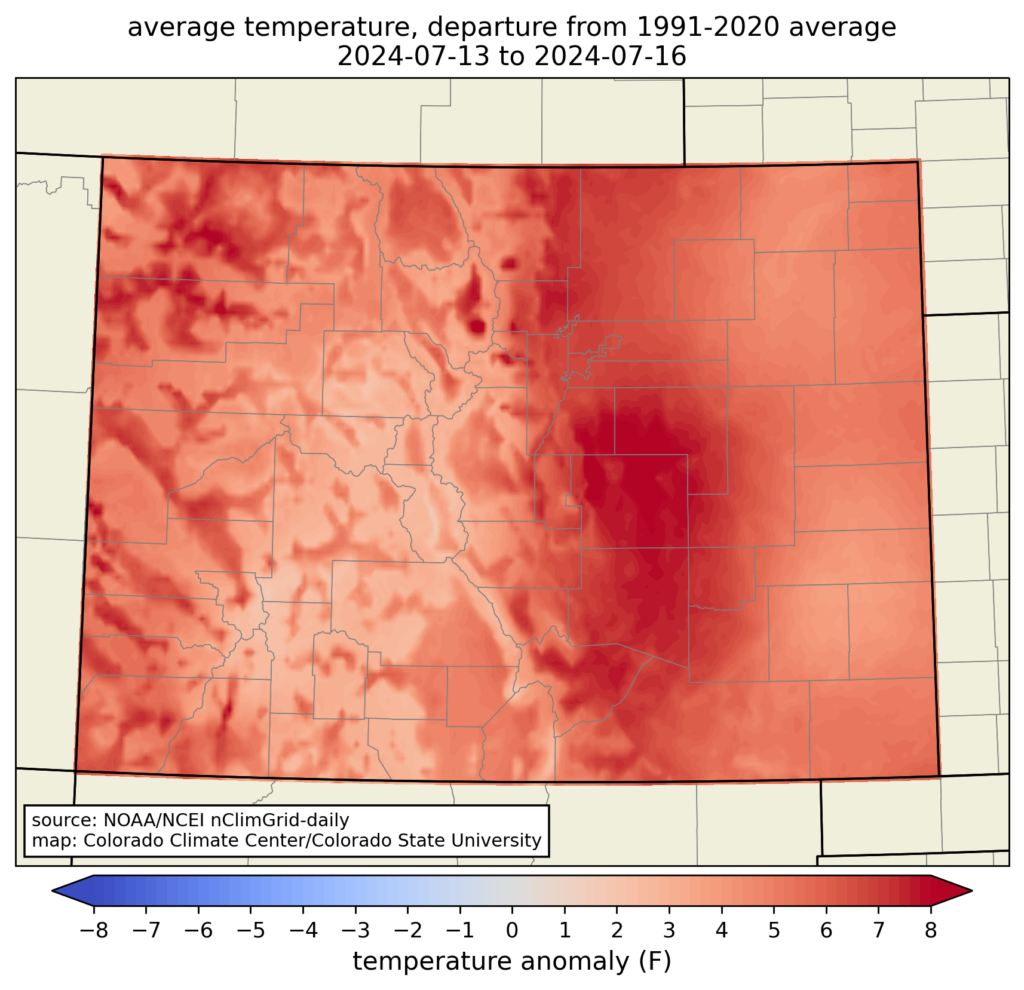

Below are maps of the average temperature for the four-day period from the morning of Friday the 12th through the morning of Tuesday the 16th, and how it compares to the 30-year “normal” for those four days.

The very highest temperatures over this period were in some of the usual places at lower elevations, like the Arkansas Valley in southeast Colorado, and the Grand Valley on the western slope. But because these are Colorado’s usual hot spots, the heat wave wasn’t as extreme compared to average in those areas. The mountains provided their usual respite from the heat. (The long-term station at Dillon made it up to 84°F, which is pretty warm for a location that has never recorded a 90-degree day.) The temperature anomaly map shows that the Urban Corridor saw the most unusually hot conditions. From the Palmer Divide down through Pueblo County, most locations were more than 8°F above average over these four days.

How does this compare to past heat waves?

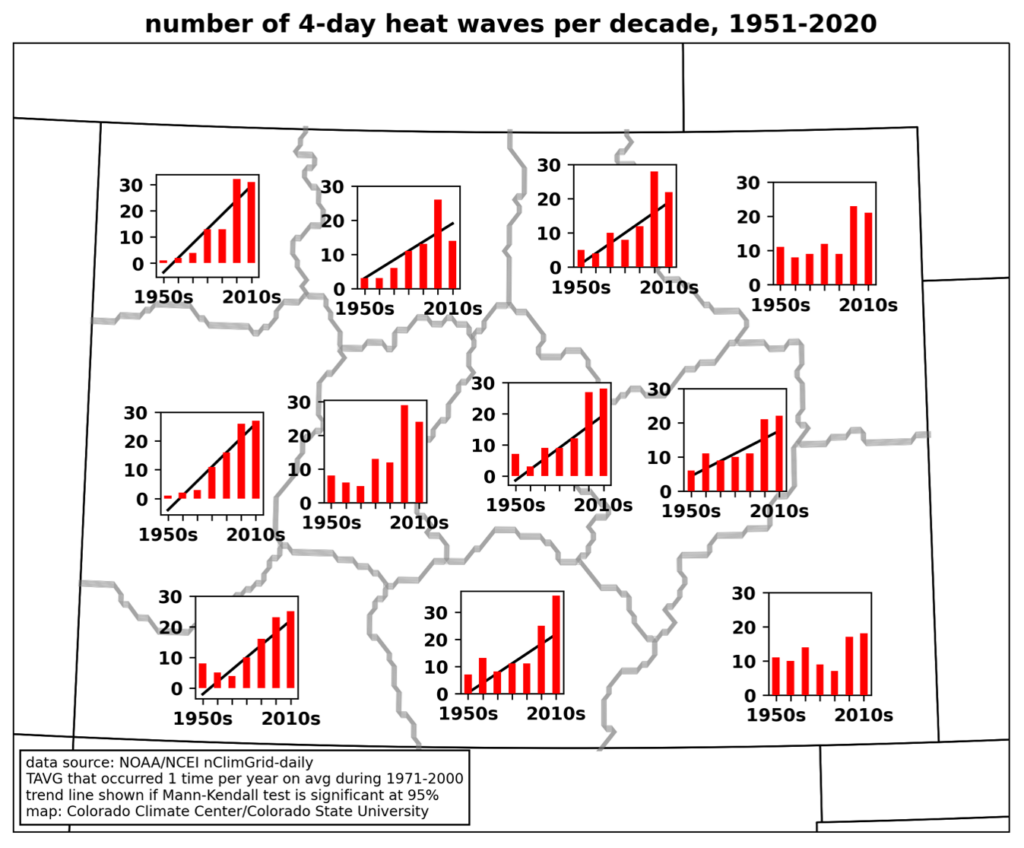

To address this question, we will build upon the analysis in the Climate Change in Colorado report, which looked at trends in four-day heat waves using NOAA’s nClimGrid-daily dataset, which goes back to 1951. In that analysis, we divided up Colorado into 11 alternate climate divisions, which better represent climate variability than the official divisions that are defined by river basins. (Interested in the details on this? We just had a paper published describing the method and results.) The map below shows where this heat wave ranked in those alternate climate divisions.

It wasn’t a record-breaker in any of the regions, but in the Northern Front Range and Pikes Peak regions, it was a top-10 four-day heat wave. Averaged across the entire state, it ranked as the 14th hottest 4-day heat wave since 1951. So, perhaps not one for the history books, but still worthy of the attention it received. You might then wonder, when were the heat waves that ranked at the top?

Pretty much everywhere in the state, the top-ranked four-day heat wave was from June 24-27, 2012. During this time period, multiple intense wildfires were raging across the state, including the Waldo Canyon fire that devastated neighborhoods on the west side of Colorado Springs. In second place statewide and in both the Pikes Peak and Northern Front Range climate divisions was in July 2005. Fort Collins set its all-time record high of 103°F during this heat wave. Mid-July of 1954 also shows up on these lists: many Front Range stations had their longest streaks of 100-degree days during that heat wave, although the nighttime lows were a bit cooler than the others so it doesn’t rank at the top overall.

What about the 1930s? What about climate change?

The nClimGrid-daily dataset, which features consistent data processing to allow for analysis of long-term changes, only goes back to 1951, which means it does not include the “dust bowl” era of the 1930s, during which intense heat and drought afflicted the Great Plains. At some individual long-term stations on Colorado’s eastern plains, heat waves in July of 1934 and 1936 still rank as hotter than those in more recent years (although at other stations, those records were surpassed by the June 2012 heat wave.) Grand Junction’s hottest 4-day period came in late July of 1931. Bob Henson and Jeff Masters at Yale Climate Connections recently published an insightful article on why the 1930s were so hot in North America, which includes the effects of poor soil management practices in the Great Plains.

We also know that the climate is warming, and that the frequency of heat waves is increasing in the western US. Most regions of Colorado saw significant increases in the number of heat waves from 1951-2020 (the exceptions being the central mountains, and the northeastern and southeastern plains). And these trends continue: the right panel below shows an updated graph for the Pikes Peak region through the present. The first 3+ years of the 2020s already had 12 heat waves in this region, which is more than than any full decade between the 1950s and 1990s. Future climate projections show that the frequency of heat waves is expected to increase much more, even in a moderate-emissions scenario.

Overall, what we’ve seen in Colorado isn’t that the most-extreme heat waves are getting more extreme. Record-smashing events are very rare even in a warming climate, and when air masses are hot enough aloft to have the potential for record-breaking heat, they often have just enough moisture to produce clouds and storms that reduce the surface temperature by a degree or two. Instead, what we’re seeing is a steady increase of heat: heat waves that would have been few and far between in the 20th century are now becoming commonplace. (I was able to do an extended interview on this topic on Colorado Public Radio’s Colorado Matters program that you can listen to here.)

A concluding note is that even with this heat wave in the middle of the month, July as a whole has not actually been especially warm across Colorado. Many stations are near to even a little below normal for temperature for the month, with the refreshing weather around the 4th of July and the cooler, wetter conditions this past weekend. However, the last week of the month looks like it will bring more hot, dry weather. This may end up putting July above average for temperature when the month concludes, and could add to the tally of heat waves in Colorado as well.