The midwest and south have been very active with severe weather lately, but it’s been relatively quiet here in Colorado so far. But we’ve reached the middle of May, which is the time of year when the threat for severe thunderstorms and tornadoes in Colorado rises rapidly. In this blog post, we’ll walk through some of the interesting aspects of Colorado’s severe weather climatology, and what history shows about what we could expect in the coming months. (If you like to explore data on your own, you can jump right over to the set of severe weather maps and graphs on our website.)

Where does severe weather tend to happen in Colorado?

First, let’s look at where severe weather happens in Colorado. (Below is a static map, but do check out the interactive map on the website where you can zoom in, select specific hazard types, etc.) The first thing you likely notice from this map is that severe storms happen a lot more frequently in eastern Colorado than on the western slope. This probably isn’t a huge surprise. There are four ingredients required to get severe thunderstorms: moisture and instability in the atmosphere, a mechanism to lift the air, and vertical wind shear (the change in wind speed and/or direction as you go up in height). Those ingredients are in place a lot more often in eastern Colorado than to the west — especially the moisture and instability. It’s tough to get enough moisture for really intense thunderstorms up in the high country.

Now, if you look even closer at the map of reports, you might notice some other interesting patterns. For example, in southeast Colorado, can you pick out Highway 50? Your eye might also be drawn to clusters along the Front Range urban corridor, or even other roads. There’s not any reason to believe that hail falls more frequently on highways than in open fields: instead, this demonstrates that the primary source of severe weather data is reports made by people, so there are more reports where people tend to be! (More of them in cities and on roadways, fewer in rural areas away from towns and major roads.)

When does severe weather tend to happen in Colorado?

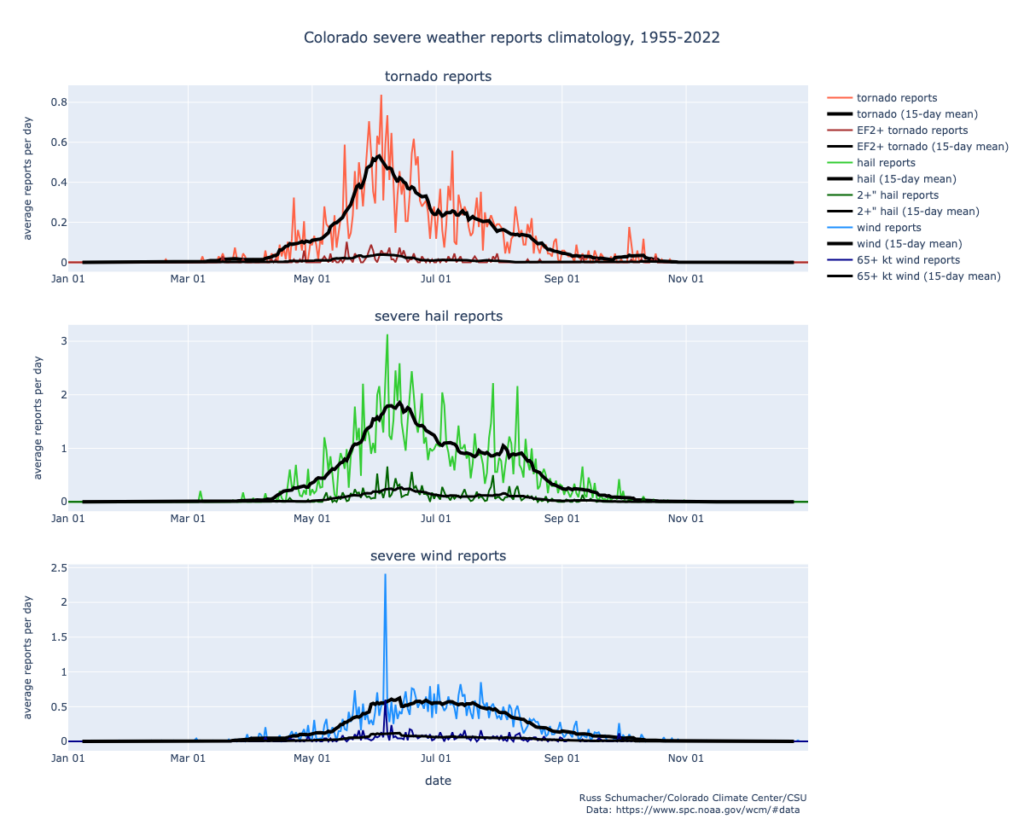

Next, we can take a look at when during the year that severe weather reports tend to happen. The black lines in these graphs show a smoothed version of the average number of reports per day. For tornadoes, the frequency ramps up through May and reaches a peak in early June, with a slow decline through the summer and into the fall. The graph for severe hail looks similar, but shifted a little later: the peak is in mid-June. The graph for severe wind reports looks a little strange, though, with a big spike on a particular day. That spike comes from the unusual derecho that swept across the country on June 6, 2020. Just in Colorado, there were 137 reports of severe thunderstorm winds (58 mph or stronger) and 36 reports of winds exceeding 75 mph on that one day, far more than any other day in Colorado records.1 That single storm system was able to alter what the severe weather climatology looks like in Colorado!

Another way to look at the data, which smooths out the effect of individual rare events, is “severe weather days”: the number of days that had one or more report of a particular hazard. The tornado and hail graphs look pretty similar to the ones above, but now the wind graph is better behaved. It shows that severe thunderstorm wind gusts are more frequent later in the summer, with a peak in early to mid-July. (An important note is that this only considers wind gusts produced by thunderstorms. Other types of intense wind tend to happen in the winter and spring.)

2023 was a very active year

We’re still awaiting the final compilation of data from NOAA for 2023, but we know that it was one of the most active years for Colorado severe weather in recent times. You might remember the Red Rocks hailstorm, the historic number of tornadoes in northeast Colorado on June 21, the unusual late-night hailstorm on June 28, or the Yuma County tornado on August 8 that was rated EF-3. Later in the evening of August 8, a new state record hailstone, 5.25 inches in diameter, was collected in Yuma County by a storm chaser.

Especially when it comes to hail, 2023 was a year for the record books, with the largest number of reports on record across every size category. (Keep in mind, though, that hailstorms have not been consistently recorded over time, and population has grown, so it’s tough to look at trends of hail reports over the long term. The 2023 data are also still awaiting final confirmation.)

How to get severe weather warnings; how to submit reports

If severe weather is in the forecast, it’s important to have more than one way to get warnings from the National Weather Service. Make sure that Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA) are active on your phone. Get a NOAA Weather Radio, especially for times when you might be outside of cell service, like when camping. Follow your local broadcast meteorologists and your local National Weather Service office. Think about the safe place where you, your family, and your pets can go if a warning is issued.

If severe weather happens to occur in your area, you can also help by reporting what happened to the National Weather Service. They accept reports over social media, or if you’re especially dedicated you can get trained to be a Skywarn spotter, submit reports on your phone using mPING, or join the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail, and Snow (CoCoRaHS) network where you can submit detailed information about hail, heavy rain, and other hazardous weather. All of these reports are useful both for knowing what is happening while storms are ongoing, and for researchers to understand how to make better forecasts and warnings in the future.

In future posts, we’ll take a deeper dive into some of the most unusual and highest-impact storms that have occurred in Colorado in its history, and other interesting aspects of the severe weather climatology.

Further reading

For further reading, check out this paper by former CSU PhD student Sam Childs:

Childs, S. J., and R. S. Schumacher, 2019: An Updated Severe Hail and Tornado Climatology for Eastern Colorado. J. Appl. Meteor. Climatol., 58, 2273–2293, https://doi.org/10.1175/JAMC-D-19-0098.1.

- The previous highest number of thunderstorm wind reports on a day was 30 severe reports (58+ mph), and 7 “significant” (75+mph) severe reports. ↩︎