The Colorado River is the lifeblood of the desert southwestern United States. Its water is used by a population of over 40 million people, is an important source of hydropower, and is the source of irrigation for a portion of the United States that produces a wide variety of specialty crops. Our beautiful state is home to some of its most productive tributaries. The Colorado Headwaters, Gunnison, San Juan, and Yampa River Basins, all in western Colorado, combine to produce over 50% of the Colorado River’s average annual discharge.

What makes these river basins so productive? Primarily it is snowpack accumulating throughout the cold season (November-April), which melts in the spring and feeds our thirsty lakes, streams, and reservoirs, including trans-basin diversions all the way from Denver to Los Angeles. Some of the Colorado River’s water comes from groundwater and summertime precipitation (an estimated 10-15% according to the Colorado River wiki), but the river is primarily a snow-fed river.

In recent years and decades the Colorado River system has become strained. A combination of climate change, climate variability, and population growth has lead to water demand outpacing water supply along the river system. When this happens curtailments are inevitable; agricultural producers, municipal water managers, hydropower producers, and other water users need to know how much water will be available for the season ahead so they can plan accordingly. To answer this question, water users turn to water supply forecasters, like the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center (CBRFC), and the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), for answers. April 1st water supply forecasts are crucial to water managers. April 1st is near peak snowpack season, and important benchmark date to those planning for the coming runoff season

April 1st water supply forecasts, such as those produced by CBRFC and NRCS, are fundamentally built around physical and statistical relationships between high elevation precipitation and snowpack measurements in the winter/spring (primarily from the Snowpack Telemetry Network), and gaged streamflow measurements in the spring/summer. After all, the Colorado river is a snow-fed river. This process typically works very well, but 2020 and 2021 yielded much lower than normal runoff despite near normal snowpack at the beginning of April. This rang alarm bells throughout the basin, and raised questions about the role of antecedent soil moisture conditions in the following season’s runoff. Theoretically, if soils are dry at the start of winter due to warm summers and dry autumns, this should reduce runoff in the coming season. As winters snow melts, the water would have to replenish dry soils before filling lakes, streams and reservoirs. 2020 and 2021 were also impacted by dry conditions in western Colorado in April and May. According to the National Centers for Environmental Information April 2021 in particular was the driest April on record for western Colorado.

Both antecedent soil moisture conditions and weather conditions following peak snowpack season negatively impacted western Colorado’s water supply forecast skill in 2020 and 2021. Soil moisture negatively impacted forecasts because it was lower than normal, and not included in all water supply forecast models (it is parametrized in CBRFC’s forecasts). Future weather impacted these forecasts because April and May precipitation were low, and weather forecasting skill is low beyond 7-10 days, so future weather cannot effectively be built into a water supply forecast. Knowing which one of these factors impacted water supply forecasts more is a paramount question because the answer dictates the best pathway for improving forecasts going forward, and how difficult that path will be. Water supply forecast errors from missing or inadequate soil moisture data can be remedied with soil moisture models and observations. Water supply forecast errors stemming from currently unpredictable future weather will persist in the absence of research that adds skill to long-term weather forecasts and seasonal climate outlooks.

With funding from the National Integrated Drought Information System (NIDIS) the Colorado Climate Center conducted a study to evaluate the role of both soil moisture/groundwater, and future weather after the date of a water supply forecast in predicting spring runoff. To do this, we created hindcasts of April–August streamflows using SNOTEL snowpack and precipitation data from 1981–2021, inputting modeled soil moisture and groundwater data to predict streamflow. In this case, “hindcast” refers to a prediction of streamflow in a previous subset of years using a statistical model that was trained based on a separate subset of years. In this way, we mimicked an actual water supply forecasting environment without including the known answer into the model. Special attention was paid to hindcasts made using October-March data (See the AMS article for a more detailed explanation of the methods).

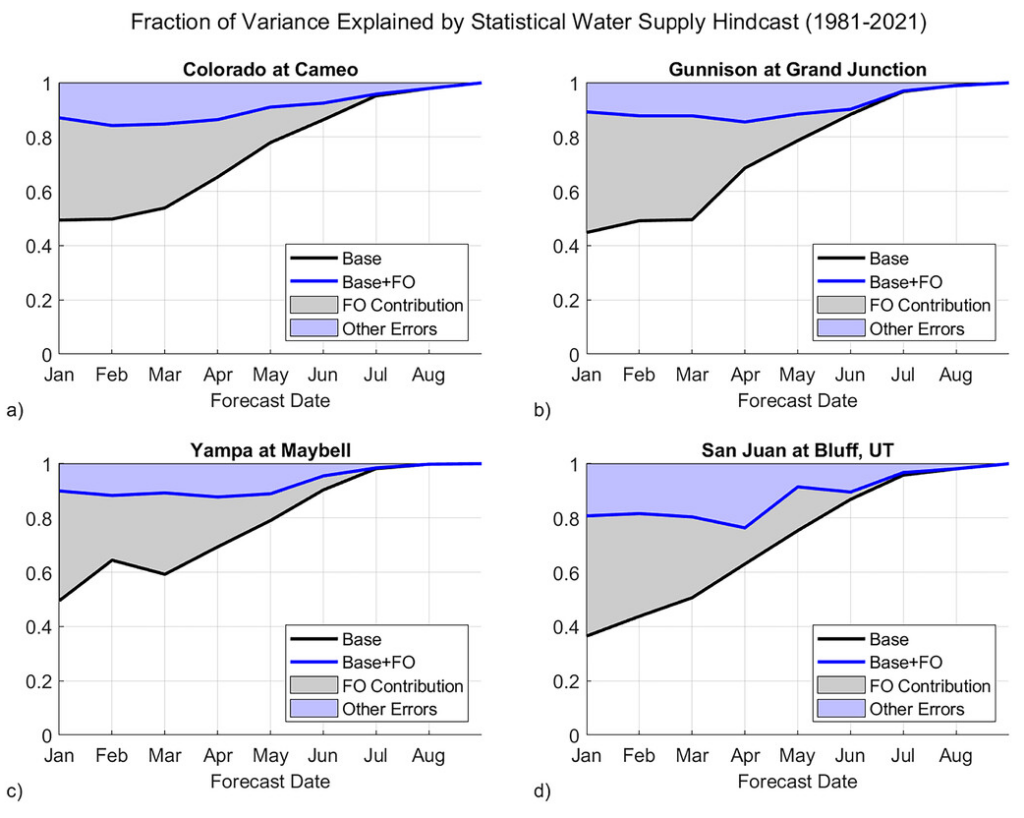

This study found that, on average, basin soil moisture and groundwater data from across the western Colorado did not contribute significantly to the skill of hindcasts. Future weather explained most of the error in water supply hindcasts made both on and before April 1st (plot 1). 2020 and 2021 were exceptional years. Both 2020 and 2021 were preceded by a hot, dry summer and a dry fall in western Colorado. As a result, hindcasts made with soil moisture and groundwater data were more skillful than those made without (tables 1 and 2).

Plot 1: Fraction of variance in April–August streamflow explained by statistical hindcasts (1981–2021) with future weather data (blue), and without future weather data for the remainder of the water year (black). Gray shaded area represents improvements in streamflow hindcasts to be gained from future weather data, aka: foresight of observations (FO). The blue shaded area represents error from other sources. Source: Goble & Schumacher 2023.

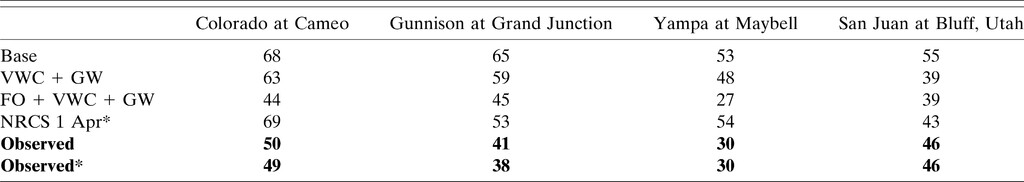

Table 1: Hindcasted percent of 1981–2019 average streamflow from hindcast sets Base (snowpack and precipitation only), including soil moisture information (VWC + GW), and including both soil moisture and future weather information (FO + VWC + GW) for 2020 compared to NRCS April 1st forecast and observed flow. An asterisk indicates the forecast/observation was for April–July, not April–August. Observed flows appear in bold. VWC = volumetric water content. GW = groundwater. FO = foresight of observations. Source: Goble & Schumacher 2023.

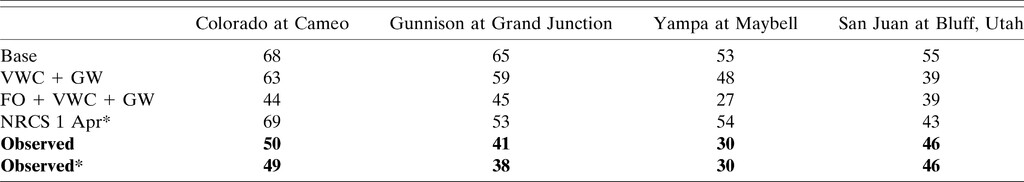

Table 2: Hindcasted percent of 1981–2019 average streamflow from hindcast sets Base (snowpack and precipitation only), including soil moisture information (VWC + GW), and including both soil moisture and future weather information (FO + VWC + GW) for 2021 compared to NRCS April 1st forecast and observed flow. An asterisk indicates the forecast/observation was for April–July, not April–August. Observed flows appear in bold. VWC = volumetric water content. GW = groundwater. FO = foresight of observations. Source: Goble & Schumacher 2023.

The long-term issues plaguing the Colorado River system aren’t going anywhere. Climate change, climate variability, and population growth will continue to challenge the status quo operations of this resource. The results of this study are important because they demonstrate that there is a clear ceiling on how skillful we can expect water supply forecasts to be for our precious rivers in western Colorado. Marginal improvements may be possible though more thorough and accurate incorporation of soil moisture data in water supply forecasts. However, April 1st water supply forecasts will continue to face a wide array of uncertainty unless the accuracy of sub-seasonal-to-seasonal forecasts can be greatly improved.

Article Citation: Goble, P. E., and R. S. Schumacher, 2023: On the Sources of Water Supply Forecast Error in Western Colorado. J. Hydrometeor., 24, 2321–2332, https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM-D-23-0004.1.