A recent email query about renewable power got me thinking about where we produce renewable power and why. The reasons are complicated. However, the weather is critical in determining where we generate renewable energy such as solar and wind power. I’ll be candid enough to say that I like renewable power, but my goal for this blogpost is not to comment on the merits of generating electricity one way or another. My goal is simply to share a couple maps from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory and discuss why we see the patterns we do.

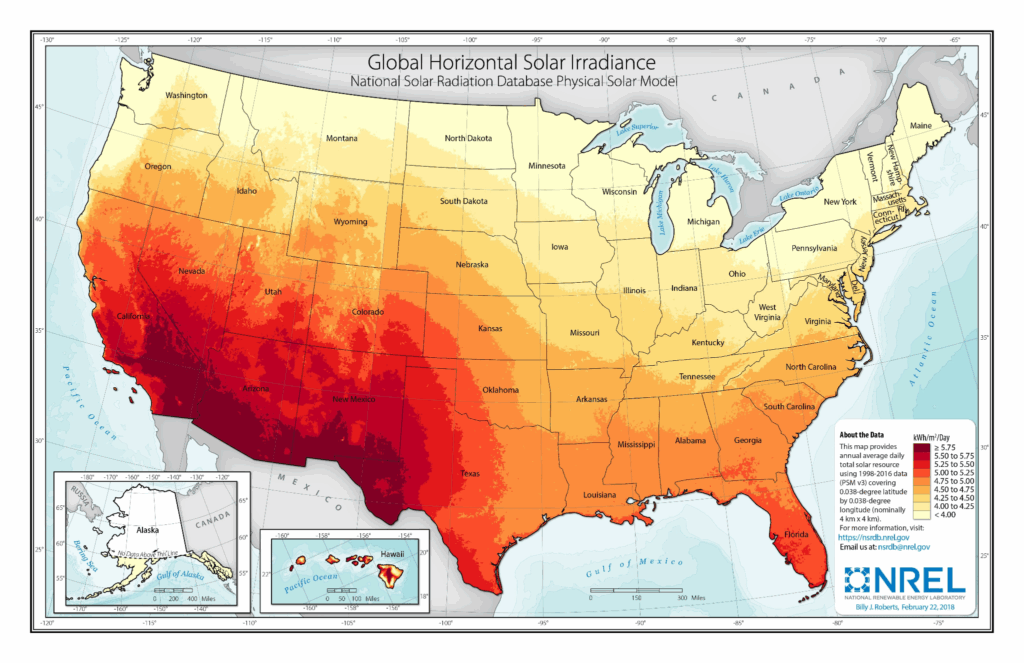

Solar Power: Solar power production potential is determined by geographic factors such as latitude altitude, and weather. Figure 1 below, from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory shows “Global Horizontal Solar Irradiance” across the Contiguous United States. For practical purposes, we can think of this as “solar power production potential,” or even more simply “how much sunlight do you get?”

Figure 1: Global Horizontal Irradiance across the Contiguous United States. Source: National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

Perhaps the most obvious pattern in Figure 1 is the difference between the northern and southern United States. The “Sun Belt” is aptly named. The southern United States receives more direct sunlight than the northern United States because it is closer to the equator. Northern states are blessed with nice, long summer days with plenty of sunshine hours, but sunlight pierces the atmosphere at a more direct angle at lower latitudes. Even within Colorado, we can see a difference in solar power potential from south-to-north. Areas like the Four Corners, San Luis Valley, and Comanche Grasslands (all in southern Colorado listed west-to-east respectively) stand out as sunny areas.

Altitude is an important factor as well. Even under clear skies, not all sunlight that passes through the top of earth’s atmosphere makes it to the surface. Some is scattered by particulates and some is absorbed by water vapor, dust, or ozone. Sunlight is thus less intense at lower elevations. Therefore, all else being equal, high elevation areas will have more solar power production potential than low elevation areas. You have probably felt this either hiking in our Colorado mountains or traveling down to sea level. The sun feels more intense on the skin, and it is easier to burn at higher altitudes.

Why is it that Colorado’s highest elevations do not show as high of solar production potential as the valleys? Weather. Our mountains are more likely to be shrouded by clouds due to orographic lift: As air is forced over our mountain ranges it must rise. As air rises it cools. As air cools, the water vapor in the air condenses, forming clouds, and oftentimes, rain or snow. One obvious example of the role of weather in solar power generation potential can be seen looking at Oregon. Western Oregon has a wealth of onshore airflow from the Pacific Ocean, bringing thick, low clouds and drizzle, which block sunlight. Eastern Oregon is high desert. The Cascade Mountain Range blocks clouds and moisture from moving inland. As a result, solar power production potential is much higher in eastern Oregon than western Oregon. While it is less obvious in Colorado than Oregon, some of our driest and least cloudy locations stand out. For instance, the San Luis Valley (south-central Colorado) is known as “The Land of the Cold Sunshine.” This area receives less than 10″ of precipitation annually, and has some of our highest solar power production potential in the state.

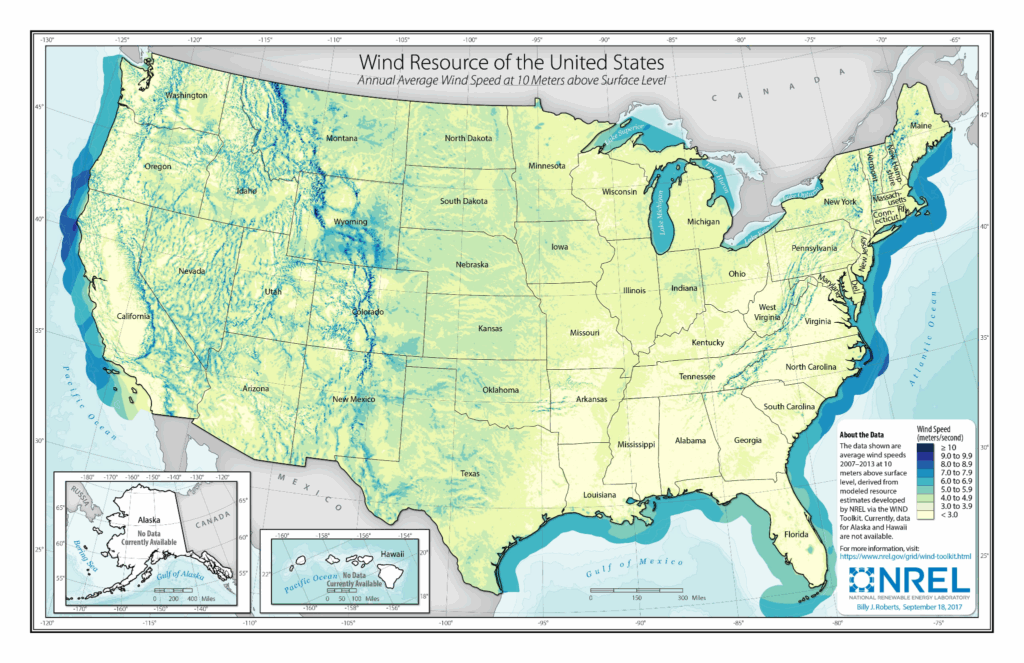

Wind Power: We can also take a look at wind power production potential across the United States, and dissect some of the drivers behind it. Figure 2 shows annual average wind speeds at 10 meters (~33ft) above ground level across the contiguous United States. A few patterns jump out here: 1. If we look at the western United States (including Colorado), higher elevation terrain does have higher average wind speeds. 2. The middle of the country is windy. 3. The east side of the Rocky Mountains is windy, including in Colorado. 4. Oh boy, our poor neighbors to the north (sorry, Wyoming)!

Figure 2: Average wind speeds at 10 meters above ground level. Source: National Renewable Energy Laboratory For what it’s worth, most wind turbines are much taller than 10 meters, thus a better reference height would be more appropriate for looking at wind power. NREL does produce maps at higher reference heights. I chose a low reference height because it is closer to the weather as we feel it.

Winds with height: On average, we do see wind speeds increase with height. This is due to increased pressure gradients, decreased friction, and reduced air density. However, Figure 2, which shows average windspeeds, does not tell the whole story. Our mountain air is only ~70-80% as dense as sea level air, so it takes stronger gusts to produce the same amount of force. Turbines at higher elevations will not generate as much power for a given windspeed as turbines at lower elevations.

The middle of the country: Figure 2 also clearly shows the “wind belt” is the high plains and southern plains around 100 degrees longitude (North Dakota down to west Texas). This area is frequently subject to sharp boundaries between air masses, or fronts. As a result, it is often windy. The terrain roughness is also an important factor. It is easier to get frequent high winds over open grasslands than forests. Eastern Colorado can be thought of as part of this wind belt, and has a relatively smooth, grassy surface with few obstacles.

East side of the Rockies: If we look at Colorado in Figure 2 we see that higher elevations are winder, but we can also see that there is an increase in winds east of the Continental Divide. There is both a sharp increase in wind speeds at high elevations immediately east of the Divide, and higher average wind speeds more generally across the eastern Colorado Plains. Our prevailing wind direction in Colorado is most commonly west-to-east, especially from October through April. Thanks to our old friend gravity, air traveling uphill slows down, and air traveling downhill speeds up. We call the days when air races down the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains downslope wind days. These blustery days are usually unseasonably warm, but can be cold if the air is coming from the north or northwest. Cross-mountain airflow does not automatically create downslope winds. Sometimes air in the valleys is too cold and dense to be forced out of the way by air moving over the Rockies. On these days we more commonly see wavy streaks of clouds instead of strong surface winds. In fact, you may also notice in Figure 2 that Denver and surrounding areas are somewhat protected, sitting in the Platte River Valley. Denver has plenty of windy days, but sometimes the strong winds pass overhead without completely mixing down to the surface.

Windy Wyoming: I love the way southern Wyoming from Cheyenne to Casper stands out in Figure 2. Southern Wyoming is the closest thing to a gap in the Rocky Mountains, so when changing weather crosses the Rockies, air gets forced through southern Wyoming like a wind tunnel. The impacts of these gap winds bleed into Colorado. For instance, Wellington is windier than Fort Collins or Denver on average. Gap winds, combined with downslope winds, also are a factor in southeastern Colorado. There are high wind warning signs on I-25 south of Pueblo as winds race down the leeward side of the Sangre de Cristos, and shoot through the gap between the Sangre de Cristos and Wet Mountains. You will see many wind turbines in this area too.

Nature sets the initial conditions for where solar and wind power can be most readily generated. Overall, Colorado experiences both plenty of sunshine and plenty of wind. Some parts of our state are especially well positioned for one or the other. Our southern valleys have strong solar production potential due to a combination of relatively low latitude, high altitude, and clear skies. Our eastern plains have strong wind production potential due to frequent exposure to strong weather fronts, relatively smooth, grassy terrain, and being downwind of the Rocky Mountains.