Our last blog post took a look at the timing of first freezes in Colorado. October has been extremely warm thus far, and many parts of the state are still awaiting their first freeze of the fall (though some of those locations may get one this weekend with the cold air moving in.) In this post, we’ll look at the data for another sign of autumn in Colorado: the first snowfall.

Colorado Public Radio’s Joe Wertz published a nice summary of when the average first snow happens in Colorado. When he asked me about this data, it turned out to be surprisingly difficult to find! The average date of first snow is not a part of the official NOAA “normals” dataset, so I had to do some calculations myself. The CPR story has an interactive map, and we now have one on our website here. I encourage you to read the story, and we’ll add a little more detail here.

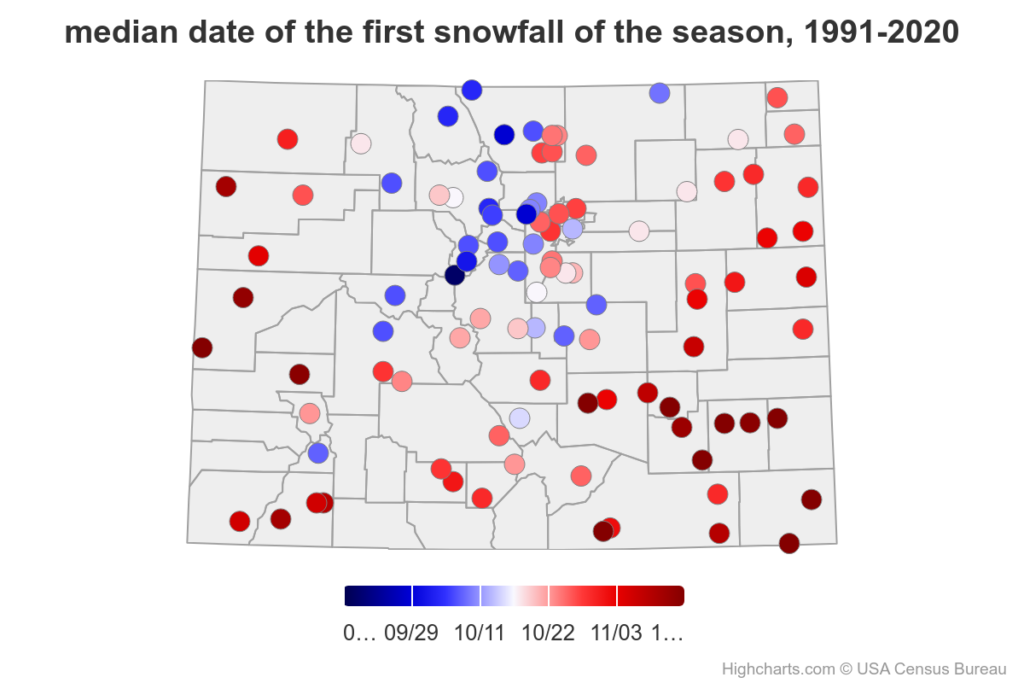

As with first freezes, the timing of the first snow varies a lot across Colorado, and it is largely tied to elevation. Among long-term climate stations, the median earliest (i.e., half of years would be earlier and half of years later) first snow is at Climax in Lake County, at over 11000 feet in elevation, on September 20. (If we had observing stations on the highest mountain peaks in Colorado, the idea of “first snow” would not be helpful, as they can get snow at any time of year.) At the other extreme are low-elevation stations in western and southeastern Colorado, where the first snow doesn’t fall until sometime in November in most years. Gateway in Mesa County, one of the warmest locations in the state, takes the prize for latest average first snow: November 25. The rest of the state falls somewhere in between. For the Front Range urban corridor, mid-to-late October is the most typical time for the first snow, while areas in the foothills and mountains are generally in late September or early October. Some mountain locations got their first snow of this fall in the September 22-23 storm: if they did, that was a little earlier than usual. And the rest will likely get their first in the current storm, which is a little later than usual.

Of course, the averages are just averages, and in Colorado we know that variations can be huge. As one example, in Fort Collins, the most common timing for the first snow is in late October, but it has happened as early as September 8, which just happened in 2020, and as late as December 13, in 1965.

Is the snow season changing?

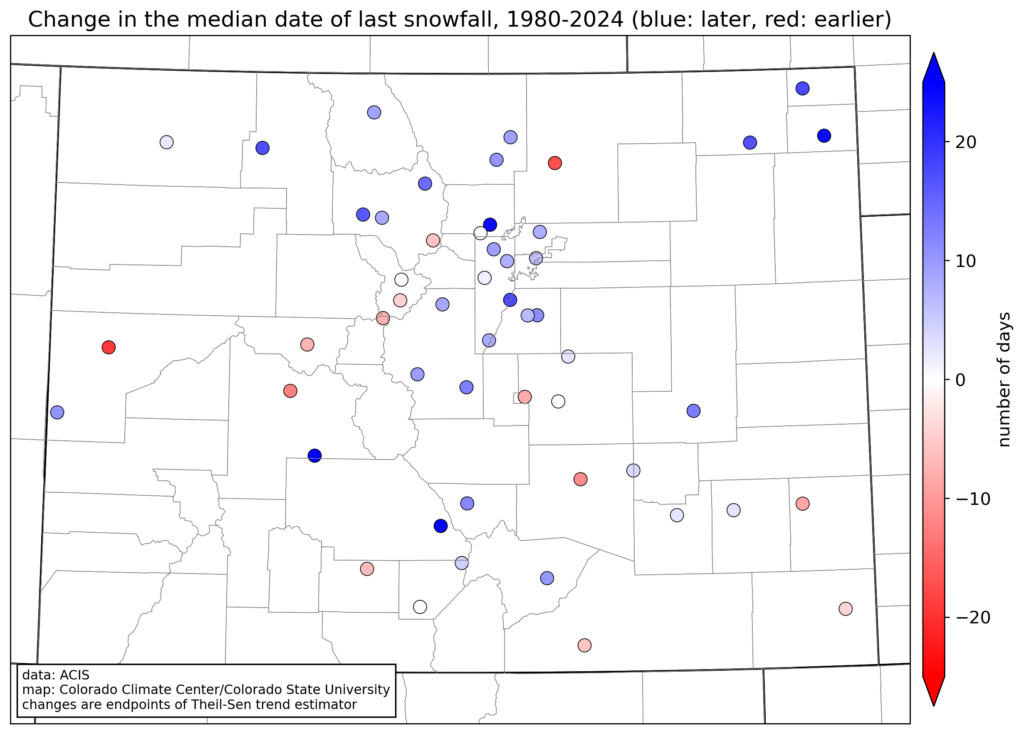

Next, we’ll take a look at the stations that have consistently reported snowfall since at least 1980, and see whether the timing of the first and last snowfall has been changing. Along the Front Range and the southeastern Plains, the timing of the first snow has been creeping later in recent decades, by a week or two at most stations. But the last snow in the spring has also been trending later. So the length of the snow season is somewhat shorter in these areas, but overall it is mainly starting a little later and ending a little later.

Mountain locations don’t show much change in timing, and there are a few mountain stations where the first snow has trended earlier over this time period. What caught my eye on these maps was far northeast Colorado: the stations at Holyoke and south of Sedgwick. (These stations have excellent records with very diligent volunteer observers.) The average first snow has shifted about a week earlier, and the last snow about 2-3 weeks later, meaning that the snow season is around a month longer now than it was a few decades ago. Cochetopa Creek, south of Gunnison, and Crestone in Saguache County, have similar trends toward longer snow seasons.

What does this all mean?

These trends in the timing of the first snow in eastern Colorado do generally line up with recent trends in temperature in Colorado, where the falls have gotten a lot warmer, but the springs haven’t warmed nearly as much. Because it needs to be relatively cold to snow, it makes sense that the odds have been tilted away from early-fall snow, but still allow snow to regularly happen in April and May. But it’s also important to take these changes with a grain of salt: as I told CPR, snow is very challenging to measure accurately, and measurement protocols have been inconsistent over time, so some of the changes may be as much a function of measurement differences than of real changes in the climate.

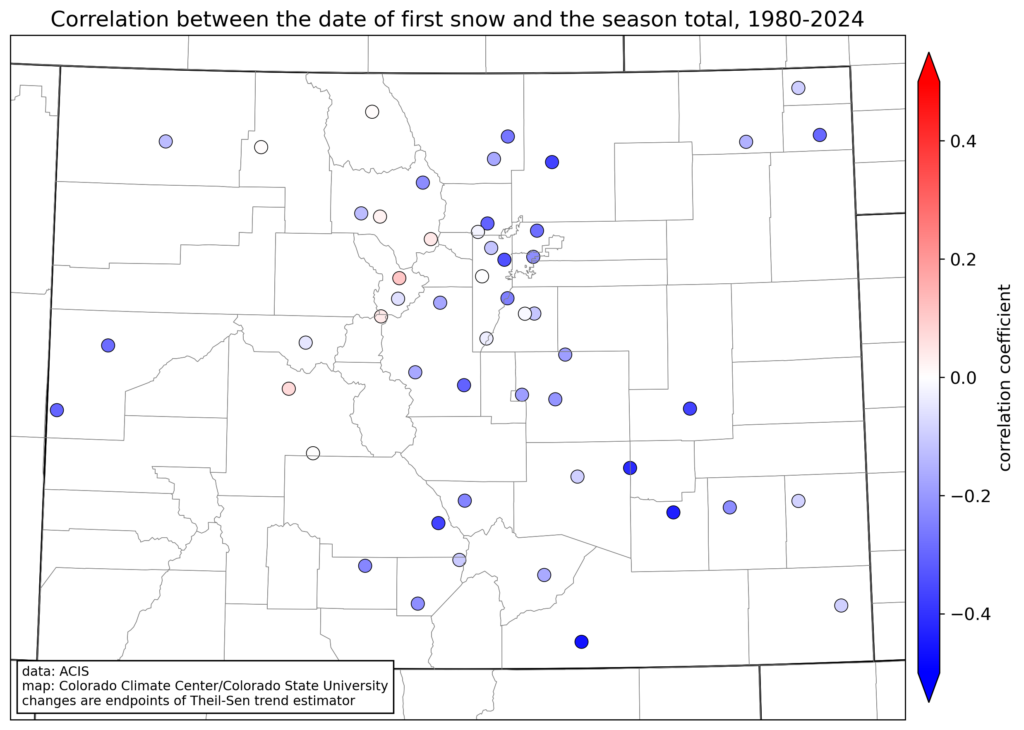

And lastly, is there a connection between whether the first snow is early or late, and the total amount of snow that falls over the season as a whole? Again, it depends where you are. In places that average a lot of snow every year (i.e., the mountains), there’s no correlation between the timing of the first snow and the seasonal total. Starting the accumulation season a week or two early or late comes out in the wash when you get hundreds of inches of snow each year. But the relationship is stronger than I might have expected in the less-snowy parts of the state.

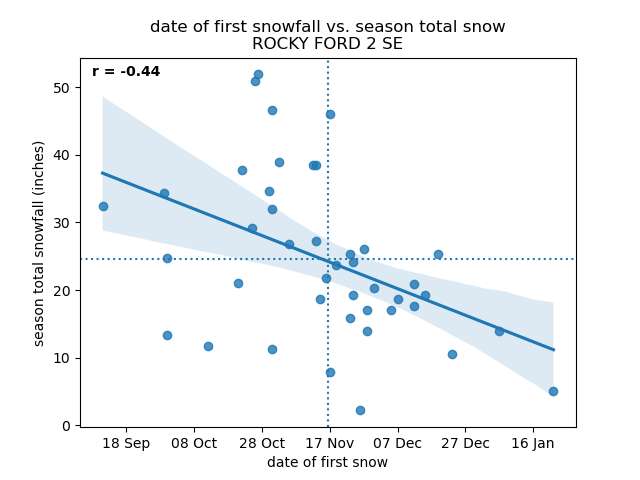

At most lower-elevation stations, there is a modest negative correlation between the date of the first snow and the total snowfall for the season (shown in blue on the map), meaning that a later start tends to mean less snow overall. On the northern Front Range, these correlations are pretty weak, but at some southeastern Colorado stations, the correlation is surprisingly strong. For example, here is the graph for Rocky Ford:

The average first snow at Rocky Ford is in mid-November, and the average total is about 25”. An early first snow doesn’t guarantee a large seasonal total: some very dry winters had an early start. But interestingly, there’s never been a big snow year at Rocky Ford if there’s no snowfall until late November (or later). This may be a bit of a “chicken-or-egg” argument: is the total lower because the snow season was shorter, or was the season shorter because the weather patterns didn’t favor snow in the fall? Either way, there is at least some connection at these lower-elevation locations.

To summarize, if you’re concerned about this year’s snowpack in the mountains, there’s no reason to be worried by the fact that there hasn’t been much snow yet – there is a very long accumulation still ahead. But if you like to see lots of snow at your lower-elevation location, the chances of a big snowfall year do start to decline when the first flakes don’t fly until late in the fall.