Northern Colorado February 3rd, 2024. Photo Credit: Bob Henson. As seen in Yale Climate Connections.

Hello, and welcome to meteorological spring (March-May). The month of February just ended, and frankly, this winter felt different. The northern Front Range of Colorado has just been through a bizarre meteorological winter. For Fort Collins, this was the second warmest and second least snowy meteorological winter since the beginning of the 21st century, and certainly warmer and less snowy than the historical past. At the same time, precipitation (the combined accumulation of rain and melted liquid from snow/ice) has been well above average this winter. The official Fort Collins Weather Station winter precipitation total of 2.42” is the 8th wettest winter on record, and ranks only behind 2007 and 2016 in the last 30 years. Boulder also recorded its 8th wettest winter in over 100 years while remaining only 0.6” above the 1991-2020 average snowfall mark. Our neighbors at the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley recorded their 3rd warmest winter, but with 151% of normal precipitation. On top of this, winter 2024 has also been speckled with rain only events, freezing drizzle, and a very heavy, spring-like rain snow mix. Is this a sign of things to come? Will rainy, drizzly, sloppy winters replace the fine, snowy powder of our past? Let’s dig into the numbers and the literature to find out.

Winter Rain Only Events

Rainfall events during the winter months on the northern Front Range of Colorado are perhaps more common than some realize. Since 1951 there have been 80 rainfall events with no measurable snow for Fort Collins, and 95 for Boulder. That is an average of 1.0-1.5 rain only events/meteorological winter. Fort Collins and Greeley had three such events this year (Boulder only one). There is no statistically significant trend in winter rain events over this time. If somebody says “it never rains in northern Colorado during winter” be skeptical.

One reason we may be inclined to believe winter rain is rare in Colorado is these events generally aren’t memorable. Precipitation accumulations are almost always small. 80-90% of rain-only winter events tally less than one tenth of an inch of precipitation. Fort Collins, Greeley, and Boulder have never seen a rain event greater than half an inch during winter. The largest rain only value occurred in Boulder on January 18th, 1974 (0.43”).

Freezing Rain/Drizzle

We also experienced a freezing drizzle event this winter on February 16th, 2024. This is not the only winter freezing drizzle events in recent years: Northern Colorado also saw freezing drizzle on January 24th, 2017, January 19th, 2022, and March 7th, 2014 (though this last date falls just outside the scope of “meteorological winter”). Anecdotally, it feels as though these events are becoming more frequent. A couple notes on freezing rain and freezing drizzle: 1. While freezing drizzle is obviously possible for northern Colorado, true freezing rain is nearly impossible. 2. Freezing drizzle is not well archived historically. One possible source of freezing drizzle records is the Automated Surface Observing System (ASOS), a network of weather stations designed to aid aviation endeavors. Some ASOS stations do mark the occurrence of freezing drizzle, but not all, and existing records are spotty. All this to say, it is unclear whether or not freezing drizzle is becoming more likely for northern Colorado.

February 3rd, 2024 (A Spring Storm in the Middle of Winter)

February 3rd was a special day on the northern Front Range of Colorado. The official Fort Collins weather station received 1.66” of precipitation between 7:00 PM on the 2nd, and 7:00 PM on the 3rd (7:00 is the official weather station daily observation time). Boulder and Greeley received 1.74” and 0.74” of precipitation respectively. This was a top ten wettest storm for Greeley and a record setter for Boulder. In Fort Collins, 1.66” of precipitation is not only a record amount of moisture for any day in February (135 years of record), it single-handedly made February 2024 the wettest February Fort Collins has ever experienced. Furthermore, Greeley’s all-time wettest February storm also occurred in 2024 just one week later, but as heavy snowfall.

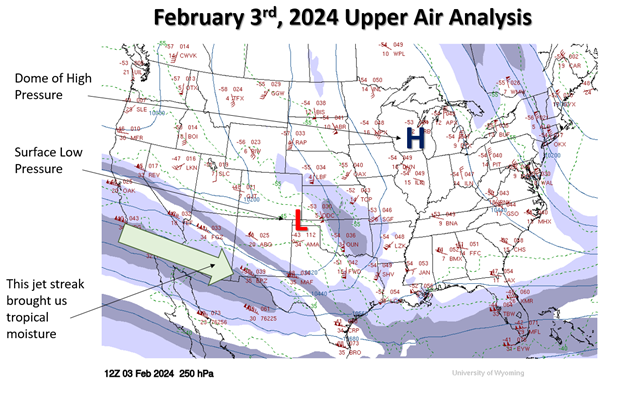

Northern Colorado locals have seen these types of rain/snow events before, but they are more of a calling card of spring. Typically, in February, the air is too cold and dry to support such accumulations. The weather pattern on this day was unique in a couple key ways allowing this event to happen. For one, the storm tapped into a corridor of tropical moisture extending all the way from the central tropical Pacific Ocean to the western United States, greatly increasing the potential for high moisture totals. These events are often called “atmospheric river events,” and are more common in coastal settings like California, Oregon, and Washington. Secondly, we experienced a split polar jet stream pattern with Colorado lying in the middle of the two currents. The southern flank of the split polar jet brought the atmospheric river to our doorstep while a high pressure airmass in the middle of the two flanks deflected the moist air back against the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains, and blocked cold arctic air from sweeping this storm out over the plains (figure 1). Both factors were important for producing such spring-like storm conditions.

Figure 1: Upper air map of Contiguous United States from the morning of February 3rd, 2024 (250 hectopascal pressure level). Wind speeds measured in knots (kts) from National Weather Service Soundings. Wind speeds contoured in 25kt intervals. 1 flag = 50 kts. Long bars = 10 kts. Short bars = 5kts. Green arrow shows position of jet stream. The “H” and “L” mark locations of high and low pressure.

Winter Precipitation and Climate Change

Our office teamed up with Jeff Lukas of Lukas Consulting to synthesize what the academic literature says about how Colorado’s climate may change over the remainder of the 21st century. This resource can be accessed here. If you have not had a chance to scan this document, I highly recommend it. We can use this document to get a glimpse into the future of winter precipitation, snowfall, and winter storms for Colorado.

Colorado has warmed, and continues to warm, significantly in all seasons due to increasing greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. Atmospheric physics tell us that warmer air can hold more water vapor, meaning there is potential for higher precipitation measurements from each individual storm under a warmer climate. We do see evidence that meteorological winters are getting wetter. Since 1950 we have seen a 3% increase in statewide wintertime precipitation. This trend is actually higher for the northern Front Range +14%, but somewhat offset by marginal decreases in western Colorado. Most climate models do suggest further increases in wintertime precipitation are likely. One experiment from our report shows an average of 6% more winter precipitation across Colorado by mid-Century with nearly 90% of the 36 global climate models used agreeing on the sign of the trend. Further increases are possible by the end of this century, and under high carbon emissions scenarios.

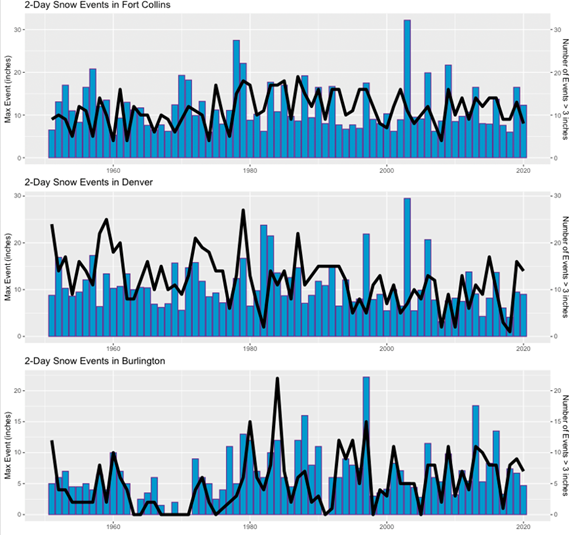

Accurately assessing trends in snowfall is more complicated. Snow measurement protocols have changed over time, muddying the waters of snowfall trend analysis. We do know average high elevation snowpack has decreased over time in Colorado, but 3”+ snowstorms on the Front Range have not. Annual maximum snowfall event totals have not fallen yet either (Figure 2). We also know that extreme cold outbreaks, which often follow winter snowstorms, are likely to continue decreasing in frequency and intensity, but will not disappear.

Figure 2: Maximum 2-day snow event per year in inches (blue bar) and total number of 2-day snow accumulations greater than 3 inches per year (black line) for Fort Collins (top), Denver Central-Park (middle), and Burlington (bottom), 1951-2020. Source: climatechange.colostate.edu

Winter storms are complex, and can be measured in a number of ways. For instance, just in recent years, we have seen the northern Front Range covered with 20-30” of snow (March 2021), a new lowest central pressure record from a winter storm (March 2019), and one of the most intense cold fronts in decades (December 2022). We have high confidence that winter will continue to get warmer on average across Colorado over the coming years and decades, but snow, extreme cold, and wildly varying conditions will not be out of the offing anytime soon.

Based on the evidence we have about climate change in Colorado, it is reasonable to hypothesize that our warming trend made this event more likely. Even so, climate models do not suggest that events like February 3rd, 2024 will become commonplace by the end of the century, even under high emissions scenarios.